Decision Making for New Warehouse Managers: Part 2 - High-Impact Decisions

Make consequential choices with structure, not instinct

Picture this: You're overseeing the implementation of a new sortation system that promises to increase throughput by 10%. The vendor is on-site, equipment is staged, and your team is ready for installation. Then, a critical safety concern emerges—the new system might compromise emergency exit pathways during peak operations. The vendor insists it's a minor issue easily addressed after installation. Your safety team wants implementation halted until the concern is thoroughly evaluated. Senior leadership is expecting improved metrics from the new system by month-end. What do you do?

This scenario represents what I call a high-impact decision—one with significant consequences, multiple stakeholders, and limited reversibility. Unlike the everyday operational choices we explored in Part 1 of this series, high-impact decisions require a more deliberate approach. While you might make dozens of Type 2 decisions (reversible, limited consequences) daily using the 2-Minute Decision Matrix we discussed last week, high-impact decisions demand a different framework altogether.

This post is the second installment in our three-part decision-making journey for warehouse leaders. In Part 1, we established foundations for handling everyday operational decisions quickly and effectively. Today, we tackle the more consequential choices that shape your operation's future. In our final installment next week, we'll explore how to build these skills into your team's culture, creating an organization that makes sound decisions at every level.

As you progress in your leadership journey, these consequential decisions become increasingly common—and how you handle them often defines your effectiveness as a leader.

When a Decision Becomes "High-Impact"

Not all important decisions are high-impact. What elevates a decision to this category is a combination of factors:

Significant consequences: The potential outcomes—positive or negative—will substantially affect operations, safety, quality, or financial performance.

Multiple stakeholders: The decision will impact various departments, shifts, or organizational levels, creating competing interests and perspectives.

Limited reversibility: Unlike everyday decisions that can be easily adjusted, high-impact decisions create lasting changes that are difficult or costly to undo.

Broader implications: These decisions often have ripple effects beyond their immediate scope, influencing other processes, people, or strategic initiatives.

Common examples in manufacturing and warehouse environments include:

Major equipment purchases or modifications

Significant process redesigns

New shift pattern implementations

Safety protocol overhauls

Substantial staffing model changes

Large-scale training program implementations

These situations typically fall into what Jeff Bezos calls "Type 1 decisions"—one-way doors that aren't easily reversible. As I explained in Decisions, Decisions: How To Make the Right Call, these choices "must be made methodically, carefully, slowly, with great deliberation and consultation."

High-impact decisions are moments of truth that reveal who you truly are as a leader. When facing the crossroads between what's expedient and what's right, the path you choose carves your legacy into the organization's memory.

The Traps of High-Impact Decision Making

Before exploring a structured approach to high-impact decisions, let's examine common pitfalls that undermine even experienced operational leaders:

Analysis paralysis: Gathering endless data without moving to decision. While thorough analysis is important, there's a point where additional information yields diminishing returns.

Premature consensus: Rushing to agreement before thoroughly exploring alternatives. This often happens when leaders feel pressure to appear decisive or when organizational culture discourages healthy debate.

Stakeholder blindness: Failing to consider all affected parties. In complex operational environments, it's easy to overlook how a decision might impact downstream processes or adjacent departments.

Recency bias: Overweighting recent experiences while undervaluing historical data. If you recently experienced a equipment failure, you might overestimate similar risks in unrelated decisions.

Solution-first thinking: Jumping to solutions before thoroughly understanding the problem. This common trap leads to addressing symptoms rather than root causes.

During my time as an Operations Manager at Amazon, I encountered many of these traps. One particularly memorable example occurred when we were implementing a new pack process that promised significant productivity improvements. I was laser-focused on the efficiency gains and moved quickly to implementation, confident in the data supporting the change.

What I failed to consider was how the process would impact quality during shift transitions. While the new approach worked brilliantly within shifts, it created confusion and errors during handoffs between teams. Because I hadn't adequately involved cross-shift stakeholders in the decision process, we implemented a solution that optimized for one metric while creating problems in another. The lesson was clear: high-impact decisions require multi-dimensional thinking and broad stakeholder involvement.

When Decision-Making Goes Wrong

History provides us with powerful examples of high-impact decision failures. Perhaps none is more instructive than the Ford Pinto case from the 1970s—a corporate decision-making disaster that illustrates what happens when structured decision processes lack ethical guardrails.

In the early 1970s, Ford was facing intense competition from imported compact cars. Under pressure to produce a lightweight, affordable vehicle quickly, Ford developed the Pinto with an aggressive timeline and strict weight and cost constraints. During pre-production testing, engineers discovered a serious flaw: in rear-end collisions, the fuel tank could rupture, potentially causing fires.

What followed was a fateful decision process that prioritized speed to market and cost control over safety. Ford conducted a cost-benefit analysis comparing the expense of a design modification (approximately $11 per vehicle) against the estimated cost of settlements for deaths, injuries, and burned vehicles. The analysis suggested that paying for lawsuits would be cheaper than fixing the design—a calculation that ignored both ethical considerations and long-term reputational damage.

The consequences were devastating: estimates suggest that as many as 180 people died in Pinto fires before a recall was finally issued in 1978. The company faced numerous lawsuits, significant reputational damage, and ultimately, the cost of a recall far exceeded what preventive modifications would have required.

The Pinto case illustrates several critical lessons for operational leaders:

Decision frames matter: How you frame a decision—purely financial versus balancing multiple factors—dramatically affects outcomes.

Stakeholder consideration is crucial: Ford primarily considered shareholders and internal financial metrics, neglecting other critical stakeholders like customers and the public.

Short-term thinking creates long-term problems: Quick wins that ignore potential longer-term consequences often prove far more costly in the end.

Process without ethics is dangerous: A structured decision-making process that lacks ethical guardrails can lead to catastrophic outcomes.

While most operational decisions don't have life-or-death implications, the principles remain relevant. Your decision framework must consider multiple dimensions—not just efficiency and cost, but also safety, quality, people impact, and long-term consequences.

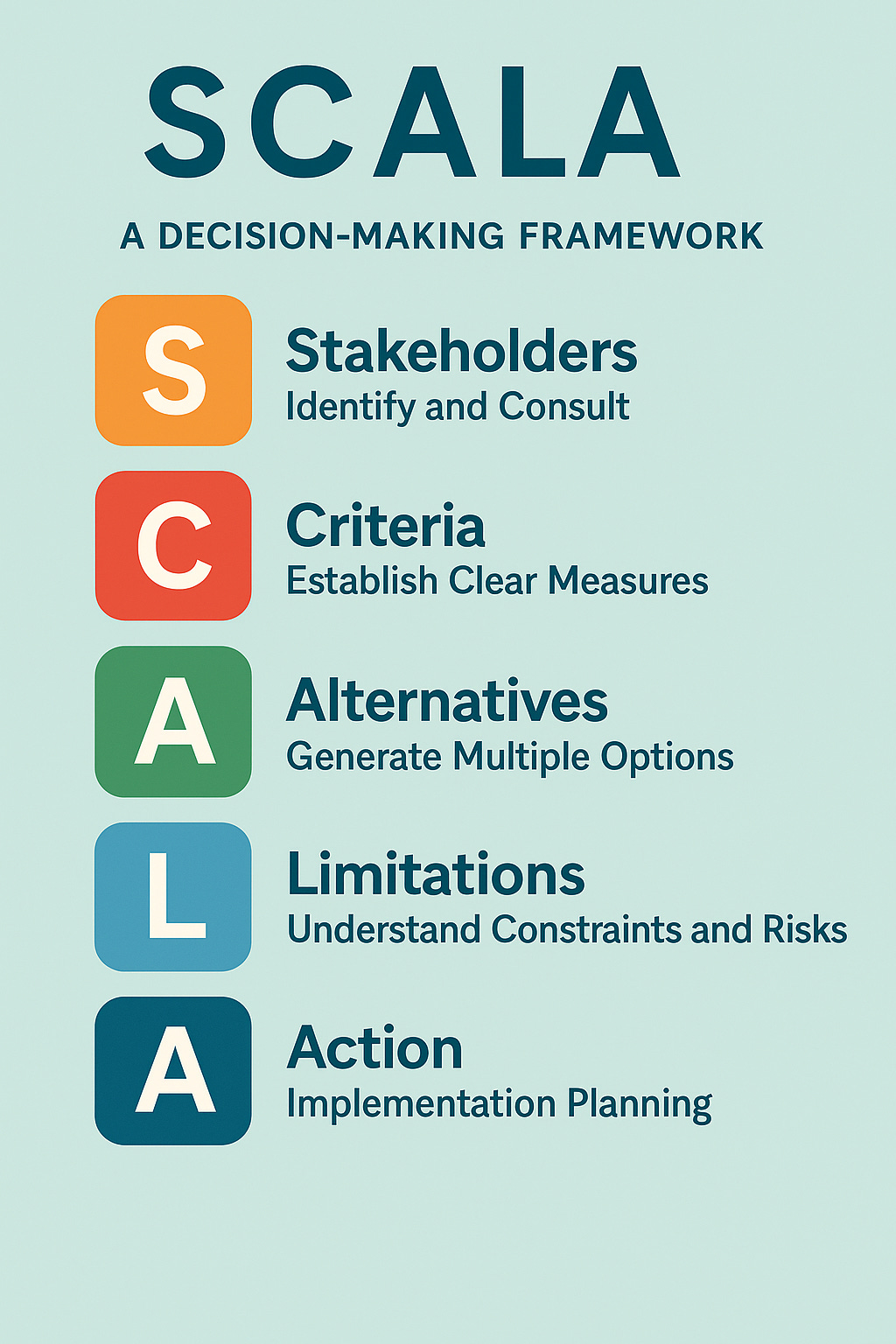

The SCALA Framework: A Better Approach

The Ford Pinto disaster demonstrates what happens when decision-making lacks critical elements: broad stakeholder consideration, comprehensive criteria beyond financial metrics, thorough alternative exploration, realistic risk assessment, and ethical implementation planning. The SCALA framework directly addresses these shortcomings by providing a structured yet practical approach designed specifically for operational environments:

S - Stakeholders: Identify and Consult

Begin by mapping all parties affected by the decision:

Direct stakeholders: Team members executing the process, upstream and downstream departments, maintenance and support functions.

Indirect stakeholders: Customers, suppliers, facilities management, upper management.

Governance stakeholders: Safety teams, quality assurance, compliance, HR, finance.

The temptation is often to limit stakeholder input to avoid complications, but this approach inevitably creates blind spots. Instead, use techniques that efficiently gather diverse perspectives:

Cross-functional stand-up meetings to identify concerns

Representative sampling instead of consulting everyone

Tiered input gathering (comprehensive for direct stakeholders, focused for others)

Clear scoping to keep discussions productive

For example, when evaluating a new conveyor system in a distribution center, your stakeholder map might include:

Direct: Inbound associates who load the conveyor, outbound teams who receive items, maintenance technicians who service it

Indirect: Inventory control tracking product movement, transportation teams affected by throughput changes

Governance: Safety team evaluating ergonomics and emergency procedures, finance approving capital expenditure

As I learned in my pack process implementation, failing to engage cross-shift stakeholders created costly quality issues that could have been anticipated with broader consultation.

C - Criteria: Establish Clear Measures

Before evaluating options, define clear decision criteria:

Operational metrics: Throughput, cycle time, efficiency, space utilization, etc.

Financial considerations: Implementation costs, ROI, payback period, ongoing maintenance costs.

People impacts: Safety improvements/risks, ergonomics, training requirements, job satisfaction.

Strategic alignment: Consistency with company values, contribution to long-term goals.

The mistake many operational leaders make is assuming everyone shares their priorities. Explicitly stating criteria forces clarity about what truly matters and prevents shifting goalposts later.

Weight these criteria based on organizational priorities. For example, in safety-critical decisions, injury prevention might carry three times the weight of efficiency gains. This weighted approach prevents important but less measurable factors from being overwhelmed by easily quantifiable metrics.

In a warehouse racking reconfiguration decision, your criteria might include:

Operational: 25% increase in storage capacity, maintain pick rate at 120 units/hour, reduce travel distance by 15%

Financial: Implementation cost under $50,000, payback period <6 months

People: No increase in manual lifting requirements, <2 hours training per associate

Strategic: Support seasonal inventory flex space, accommodate new product categories

A - Alternatives: Generate Multiple Options

With stakeholders identified and criteria established, develop multiple viable alternatives. This step is where many decision processes fail—by jumping to the most obvious solution without adequately exploring options.

Effective techniques include:

Constraint relaxation: Ask "What would we do if [constraint] weren't an issue?" then work backward to feasible solutions.

Benchmarking: Explore how other departments or facilities have addressed similar challenges.

Small-scale testing: Pilot different approaches in limited areas to gather real-world data.

Diverse input: Seek perspectives from different organizational levels and functional areas.

A minimum of three substantively different alternatives should be considered for any high-impact decision. This prevents the false choice between "do nothing" and a single proposal.

For example, when facing a persistent quality issue in a fulfillment center's packing operation, you might consider:

Option 1: Implement additional quality checks at pack stations

Option 2: Redesign the pack station layout to reduce error potential

Option 3: Introduce vision technology to automatically verify package contents

Option 4: Restructure the workflow to allow packers to specialize by product type

L - Limitations: Understand Constraints and Risks

Thoroughly assess the constraints and risks associated with each alternative:

Resource limitations: Budget caps, timeline requirements, available labor hours.

Technical constraints: System compatibility, equipment capabilities, facility limitations.

Organizational boundaries: Authority limits, approval requirements, policy constraints.

Risk assessment: Structured evaluation of what could go wrong, how likely it is, and potential mitigation strategies.

This step often reveals hidden issues that might derail implementation. As I discussed in my post on handling stressful situations, anticipating problems before they occur significantly reduces pressure during execution.

For a warehouse automation project, your limitations analysis might identify:

Resource constraints: Limited IT resources available for integration

Technical limitations: Legacy system compatibility issues with new technology

Organizational boundaries: Regional approval required for capital expenditures >$100,000

Key risks: Power infrastructure inadequate for peak demand, potential data migration issues

A - Action: Implementation Planning

The final step bridges decision and execution:

Implementation roadmap: Detailed timeline with clear milestones and responsibilities.

Communication strategy: How the decision and its rationale will be shared with various stakeholders.

Feedback mechanisms: Systems to monitor outcomes and identify issues early.

Adjustment protocols: Predetermined triggers and processes for making course corrections if needed.

Too often, operational leaders treat the decision as the finish line, when it's actually just the beginning. Without robust implementation planning, even the best decision can fail in execution.

For a shift pattern change in a manufacturing facility, your action plan would include:

Implementation timeline with training sessions scheduled before go-live

Personalized communication for affected employees with rationale and expectations

Daily metrics review for the first two weeks to catch productivity or quality impacts

Predetermined criteria for reverting to the original pattern if specific issues arise

In warehouse environments, the gap between a good decision and good results isn't just implementation—it's communication. Even the most brilliant operational choice will fail if the team members executing it don't understand the 'why' behind the change.

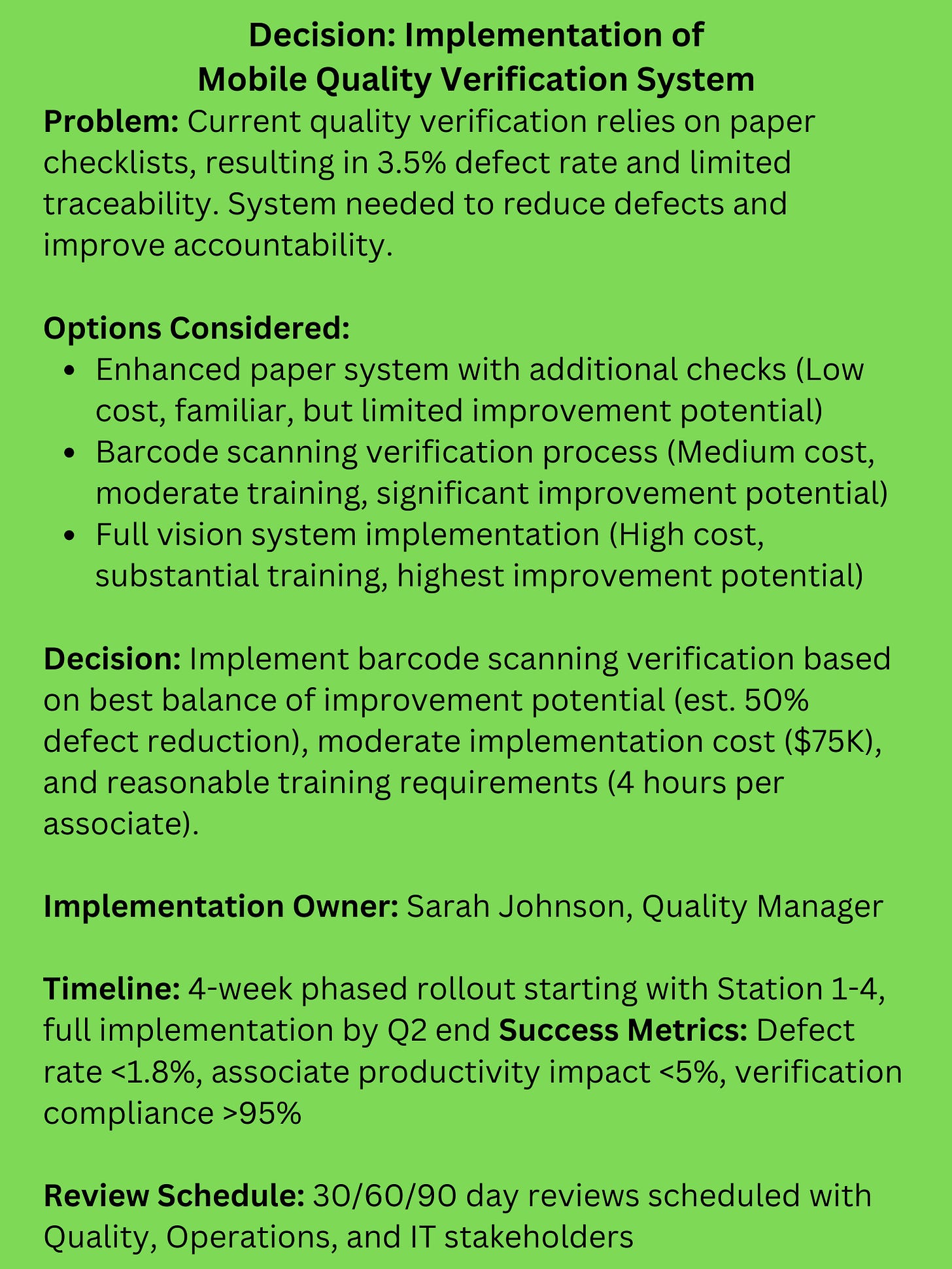

Documenting High-Impact Decisions

Unlike everyday operational choices, high-impact decisions warrant documentation. This isn't bureaucracy—it's a discipline that creates accountability and transparency, enables learning from past decisions, provides context for future leaders, and supports consistent communication. A simple one-page decision document should capture:

Problem statement and background

Options considered with pros/cons

Decision rationale with explicit link to criteria

Implementation overview and ownership

Review timeline and success metrics

This documentation need not be elaborate—a simple template can be completed in 15-20 minutes for most decisions.

For example, a decision document for a new quality inspection process might look like this:

The complementary High-Stakes Decision Worksheet accompanying this post provides a practical template you can adapt for your operational environment.

Building Support for Your Decisions

Even well-structured decisions face implementation challenges without proper organizational support. Building alignment is a critical skill that many operational leaders overlook—they assume that a logical decision with clear benefits will automatically gain support. In reality, implementation success depends on how effectively you build buy-in.

Effective support-building strategies include:

Involve key influencers early: Identify and engage respected voices whose support will carry weight with the broader team. In warehouse environments, these aren't always those with formal authority—often, they're experienced operators whose opinions carry significant informal influence. Bring these individuals into the process early, even if only for targeted consultation.

Connect to shared values: Frame decisions in terms of organizational priorities and values that stakeholders already embrace. For example, if safety is a core value, explicitly link your decision to safety improvements, even when they're secondary benefits.

Acknowledge concerns transparently: Directly address the downsides of your chosen approach rather than ignoring them. When implementing a new picking methodology, explicitly acknowledge the learning curve and potential short-term productivity dip while explaining how you'll mitigate these challenges.

Create ownership through involvement: Give stakeholders meaningful roles in implementation planning. For a significant layout change, assign respected team members to champion specific aspects of the transition.

Use pilot demonstrations: When possible, create small-scale demonstrations that allow stakeholders to see the solution in action. For process changes, implement in one area first so others can observe the benefits before full deployment.

Develop tailored messaging: Different stakeholder groups have different priorities. Customize your communication to address what matters most to each group. When explaining a new inventory management system, the emphasis for floor associates might be on ease of use, while for senior leaders it might be on improved accuracy metrics.

Build coalitions across departments: Identify allies in adjacent departments who also stand to benefit from the change. Their support can help overcome resistance and create momentum. For cross-functional changes like a new receiving process, secure visible support from quality, inventory, and operations leadership.

In my experience leading cross-functional projects at Amazon, the time invested in building support almost always pays dividends during implementation. As I explored in my post on creating a culture of openness and honesty, transparency builds the trust foundation necessary for successful change initiatives.

Leveraging Technology for Decision Support

Modern warehouse environments now have access to sophisticated tools that can enhance the decision-making process. While these tools don't replace judgment, they can significantly improve information quality and analysis capabilities:

Data visualization platforms: Tools like Power BI, Tableau, or even advanced Excel dashboards can transform complex operational data into visual insights that clarify decision criteria.

Simulation software: For major layout or process changes, simulation tools can model different scenarios before physical implementation, revealing unforeseen bottlenecks or constraints.

Digital decision documentation systems: Shared collaboration platforms like Microsoft Teams, Confluence, or specialized decision management software can streamline the documentation process and improve visibility.

Mobile feedback collection: Apps and digital forms can efficiently gather input from stakeholders across shifts and locations, expanding the perspectives considered.

The key is selecting tools that enhance rather than complicate your decision process. As I discussed in The Power of Focused Work, technology should reduce cognitive load, not increase it. Start with simple tools that address your specific decision-making challenges rather than implementing complex systems that may go unused.

From Theory to Action

Ready to elevate your high-impact decision making? Start with these practical steps:

Build a decision inventory: Review the past month and identify 3-5 decisions that would have benefited from the SCALA framework. Note patterns or weaknesses in your current approach.

Create a stakeholder map: Develop a visual representation of the key stakeholders for decisions in your operational area. Include both formal reporting relationships and informal influence networks.

Develop a personal criteria checklist: Document the 5-7 factors that should be considered in most high-impact decisions in your area. Use this as a quick reference to ensure comprehensive evaluation.

Practice structured evaluation: For your next significant decision, create a simple scoring matrix comparing alternatives against your established criteria. Share this approach with your team to model data-driven decision making.

Establish decision documentation standards: Create a simple template for capturing high-impact decisions. Use it consistently and encourage your team to adopt the same practice.

Build a "challenge network": Identify 2-3 trusted colleagues who think differently than you do. Invite them to critique your decision process before finalizing significant choices.

Schedule decision reviews: For major decisions, calendar a 30/60/90-day review to assess outcomes and capture learning. This creates accountability and builds organizational memory.

By implementing these practices, you'll build both personal decision-making capability and organizational capacity. Your team will shift from reactive choices to thoughtful decisions that advance strategic priorities while minimizing unintended consequences.

In our final installment of this series, we'll explore how to build a decision-making culture across your operation—moving beyond individual capability to create systems that support sound decisions at all levels. Until then, use the SCALA framework to tackle your next high-impact decision with confidence and clarity.

Remember that mastering high-impact decisions isn't just about operational excellence—it's about establishing the leadership presence and judgment that will serve you throughout your career.

Want to stop feeling overwhelmed by daily decisions? Join our community of operational leaders focused on practical skill development.

Follow me on LinkedIn