Process Improvement Fundamentals for New Leaders

Facilitate team improvement solutions rather than dictate process changes.

Most operations leaders approach process improvement backwards. They identify what's broken, design a solution, and then try to convince their team to implement it. This top-down approach is why most improvement initiatives fail within six months.

The counterintuitive truth is that the best process improvements come from the bottom up, not the top down. Your role as a leader isn't to be the smartest person in the room who fixes everything—it's to create the conditions where your team can identify problems and design solutions that actually work.

I learned this lesson during my years at Amazon, leading process improvement projects across multiple facilities. The initiatives that delivered lasting results succeeded because I learned to facilitate improvement rather than dictate it. The projects that failed were the ones where I thought I had all the answers.

If you're struggling with improvements that don't last or team members who resist change, this isn't about your people being difficult. It's about approaching improvement in a way that actually works.

This systematic approach to process improvement isn't just about making operations more efficient. It's about building a culture where continuous improvement becomes part of how your team thinks and operates every day.

Understanding What Process Improvement Really Means

Process improvement has become one of those buzzwords that gets thrown around in meetings without anyone stopping to define what it actually means in operational terms. Let me cut through the jargon.

At its core, process improvement is about making the work easier for your team while delivering better results for your organization. It has three essential components: efficiency (doing things faster), quality (doing things right), and sustainability (creating changes that stick).

But here's what most leaders miss: continuous improvement isn't just about making things faster. Speed without quality creates rework. Quality without efficiency creates bottlenecks. And neither matters if the improvements disappear the moment you stop paying attention to them.

The real goal is creating processes that work so well your team can execute them consistently, even on their worst days. When someone calls in sick, when equipment breaks down, when you're short-staffed—your processes should be robust enough to handle these normal operational challenges without falling apart.

The Hidden Cost of Avoiding Process Improvement

When leaders avoid tackling process improvement, they're not just leaving efficiency gains on the table. They're creating a cascade of problems that compounds over time.

Team frustration tops the list. Your best workers notice the inefficiencies. They see obvious solutions. When those solutions are ignored or dismissed, engagement drops. High performers start looking for opportunities elsewhere, and you're left managing the people who've accepted that "this is just how we do things here."

Meanwhile, those compounding inefficiencies are costing you more than you realize. Every minute wasted on a broken process gets multiplied by every person who touches that process, every shift they work, every day of the year. But five minutes times ten people times two shifts times five days a week equals over 43 hours of wasted time every week. That adds up fast.

Perhaps most damaging is the lost competitive advantage. While you're struggling with the same problems month after month, your competitors are finding ways to do things better, faster, and cheaper. Process improvement isn't optional in today's environment—it's survival.

The ripple effect on morale when obvious problems go unfixed creates a culture of learned helplessness. Teams stop suggesting improvements because they assume nothing will change. Innovation dies, and you end up with a workforce that just follows orders instead of thinking critically about how to do things better.

Learning from the Master

If you want to understand process improvement, you need to understand W. Edwards Deming. After World War II, Japan was synonymous with cheap, low-quality products. Japanese manufacturers were desperate to change that reputation, but they didn't know how.

Deming, an American statistician and quality expert, taught them something revolutionary: the problem wasn't the workers—it was the systems. He showed Japanese manufacturers how to use statistical methods to understand variation in their processes and how to design systems that produced consistent, high-quality results.

The transformation was remarkable. Within two decades, "Made in Japan" went from being a mark of poor quality to a symbol of excellence. Companies like Toyota, Honda, and Sony became global leaders by applying Deming's principles systematically.

The One Insight That Changed Everything for Me

Deming said something that has stuck with me for years: "Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets."

When I first read that, I thought it was just a clever quote. Then I started applying it to my own operation, and everything clicked.

If my pick rates were inconsistent, it wasn't because some people were lazy—it was because my system allowed for that inconsistency. If we kept making the same mistakes, it wasn't because people weren't paying attention—it was because my system made those mistakes easy to make.

This completely flipped how I approached problems. Instead of asking "Who screwed up?" I started asking "How did our system let this happen?" Instead of training people harder on the same broken process, I started asking "How can we design this so it's harder to get wrong?"

How Deming's Ideas Actually Work on the Warehouse Floor

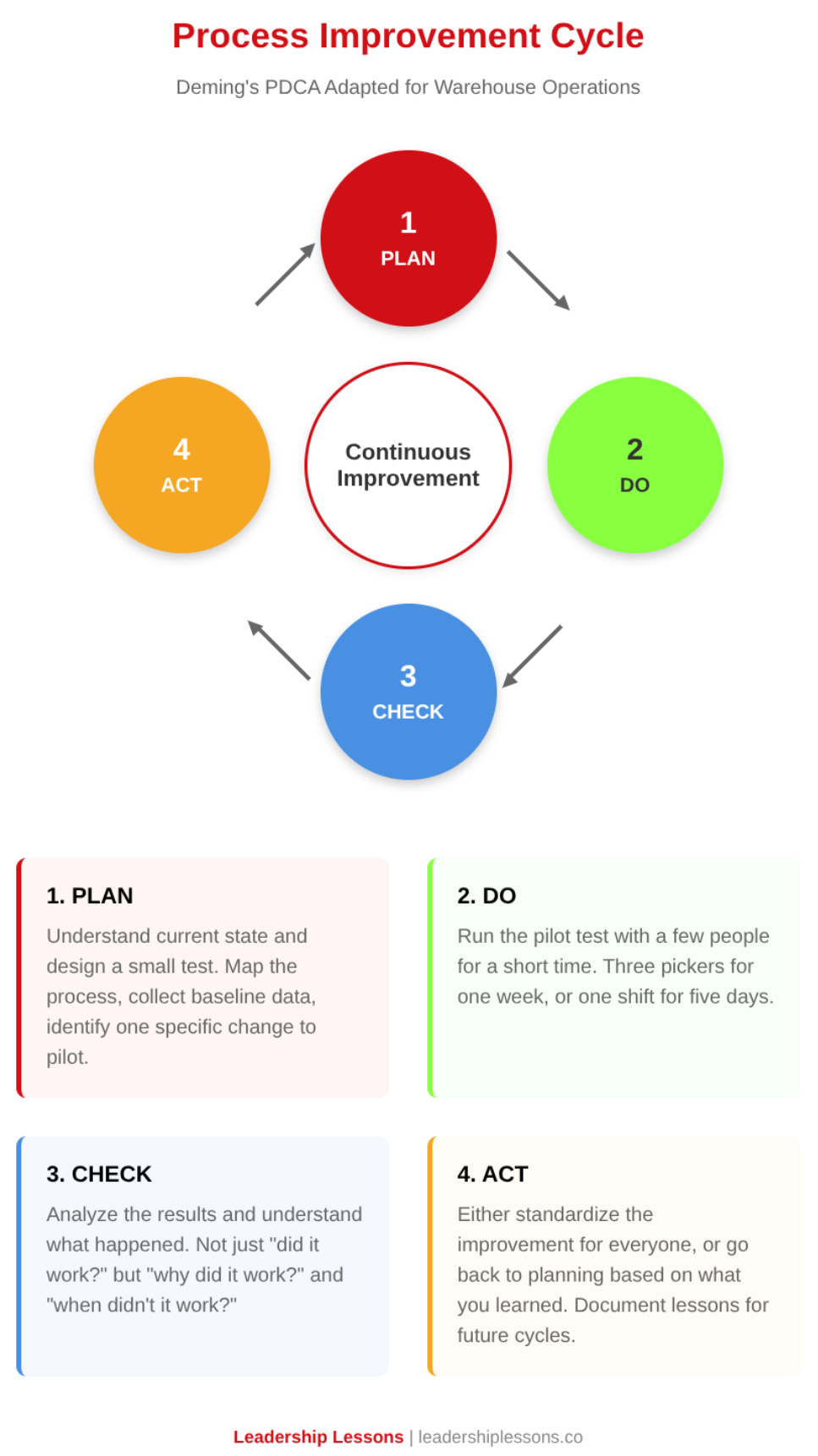

Deming taught a simple improvement cycle: Plan-Do-Check-Act. I use this constantly now, in very practical ways.

Plan means really understanding what's happening now and designing a small test. Not a complete overhaul—just one small change you can test safely.

Do means running that test with a few people for a short time. Maybe three pickers for one week, or one shift for five days.

Check means looking at the data and really understanding what happened. Not just "did it work?" but "why did it work?" and "when didn't it work?"

Act means either making the change standard for everyone, or going back to planning based on what you learned.

The key insight from Deming is that variation kills performance. When your processes produce wildly different results depending on who's doing them or what day it is, you can't plan effectively. You can't predict capacity. You can't deliver consistent service.

I learned to focus on reducing variation, not just improving averages. Sometimes making the worst performances better matters more than making the best performances even better.

Deming also taught me to build quality into the process instead of trying to catch problems afterward. In warehouse terms, this means designing workflows that make errors difficult or impossible, rather than having someone inspect for mistakes after they've already happened.

"It is not necessary to change. Survival is not mandatory." - W. Edwards Deming

My Framework for Process Improvement That Actually Works

After years of trial and error, here's the approach I use now. It's based on what I learned from Deming, but adapted for the realities of warehouse operations.

Step 1: Figure Out What's Really Happening

Before you can improve anything, you need to understand how it actually works—not how you think it works, not how it's supposed to work, but how it really works when you're not watching.

I learned this lesson when I was trying to improve our receive process. I thought I knew exactly how it worked because I had designed it. But when I actually walked it with different people on different shifts, I discovered all sorts of workarounds and variations that weren't in my documentation.

Process mapping doesn't have to be fancy. I usually just grab a notepad and follow the work. I time the steps, note where things sit waiting, and pay attention to handoffs between people or departments.

The key is distinguishing between bottlenecks and root causes. A bottleneck is where work backs up—that's what you can see. The root cause is why it backs up there—that's what you need to fix.

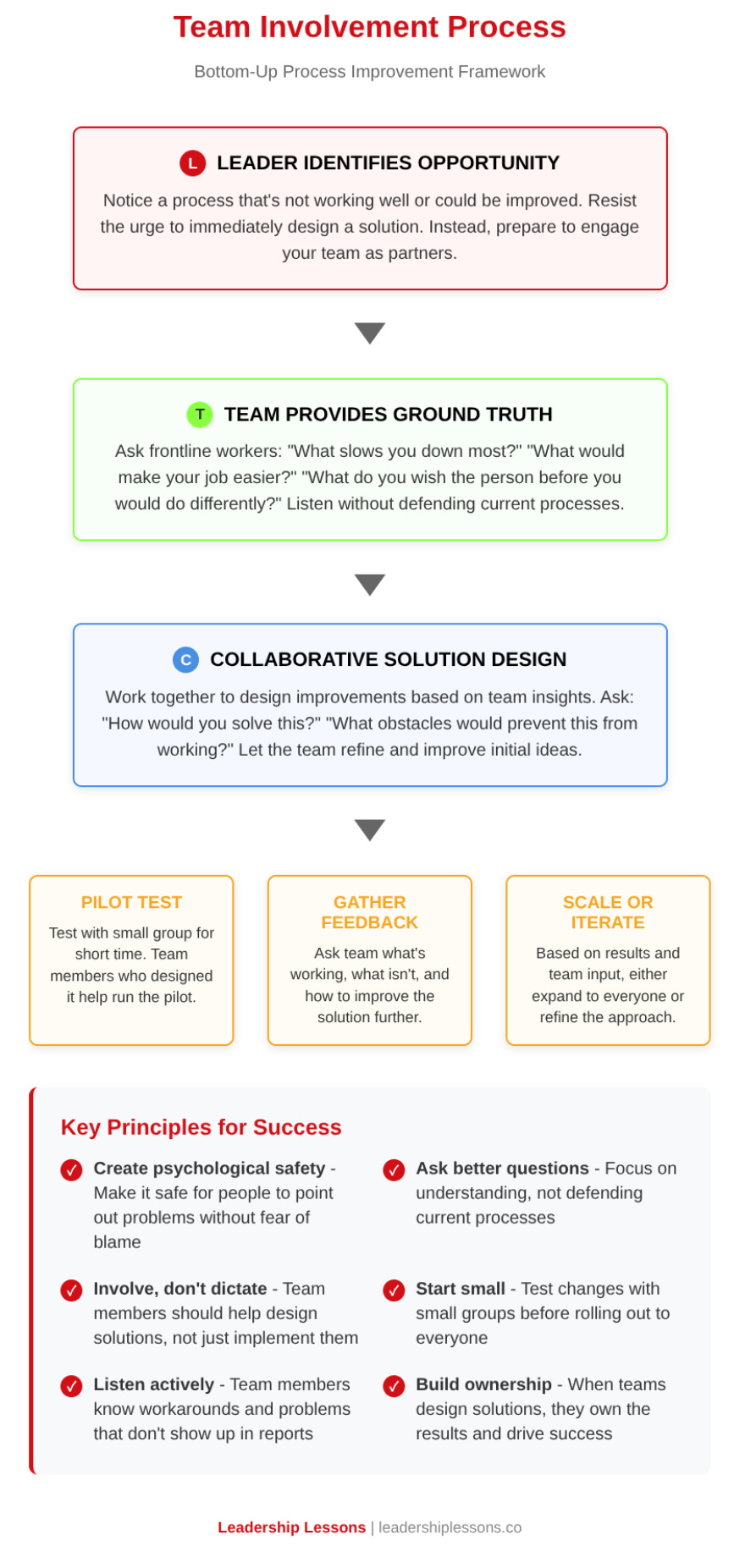

Step 2: Make Your Team Partners, Not Order-Takers

This is where I used to completely blow it. I thought my job was to be the smart guy who solved all the problems. What I learned is that the people doing the work every day know things I'll never know from observing or analyzing reports.

They know which steps in the process are actually unnecessary. They know which tools don't work as well as they should. They know the workarounds that make things function when the official process doesn't work.

Most importantly, they know which problems happen all the time but don't show up in your metrics.

I've learned to ask better questions: "What part of this process slows you down the most?" "If you could change one thing, what would it be?" "What would make your job easier?" "What do you wish the person before you in this process would do differently?"

The trick is making it safe for people to point out problems. When someone identifies an inefficiency, my first response is always "Thank you for bringing this up," not "Why didn't you mention this sooner?"

For more on building this kind of trust with your team, check out this post:

Step 3: Test Small Changes, Not Big Overhauls

I used to want to fix everything at once. Big, dramatic improvements that would solve multiple problems and impress my boss. This approach fails almost every time.

Now I focus on small, testable changes. Pick one thing, test it with a few people for a short time, measure what happens, then decide what to do next.

Pilot programs are your best friend. Choose a small group, a short timeframe, and one specific change. This lets you test the improvement without risking your entire operation.

I also learned to look for quick wins—improvements that are easy to implement and deliver obvious benefits. These build confidence in the improvement process and make people more willing to try bigger changes later.

When I proposed changing our pack process to improve rates, the initial team reaction was skeptical. Instead of pushing forward with my plan, I asked three experienced packers to spend a couple days observing the current process and suggest modifications. Their insights revealed workflow conflicts I hadn't noticed and led to solutions I never would have considered. When we implemented their refined approach—not my original idea—we saw a 12% rate increase. More importantly, the team owned the change because they had designed it. The lesson: Leaders provide the framework for improvement, but the best solutions come from the people doing the work.

Overcoming the Common Obstacles

Even with the right approach, you'll face predictable challenges. Here's how to handle the most common ones.

"We Don't Have Time for Improvement"

This is the most common objection, and it reveals a fundamental misunderstanding. You don't have time NOT to improve. Every day you leave an inefficient process in place, you're choosing to waste time rather than invest time.

Reframe improvement as operational necessity, not optional activity. Just like you make time for safety training and equipment maintenance, you need to make time for process improvement. It's part of running an operation, not something extra you do when you have spare time.

Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.

The solution is finding improvement time within existing schedules. Use slow periods for process mapping. Incorporate improvement discussions into your regular team meetings. Make improvement projects part of your employees' development goals.

For specific strategies on managing time for improvement activities, see my post on The Power of Focused Work, which covers how to protect time for important but non-urgent activities like process improvement.

Resistance from Long-Term Team Members

Long-term employees often resist change because they've seen improvement initiatives come and go. They've invested time and energy in learning the current system, and change feels like a criticism of their work.

Understanding the psychology of change resistance is crucial. People don't resist change—they resist being changed. When you involve them in designing the improvement, resistance turns into ownership.

Lead with "why" before "how." Explain the problem the improvement is trying to solve. Help people understand the cost of not changing. Make it clear that the goal is making their work easier, not just making the company more money.

Show respect for their experience and expertise. Acknowledge that they know things about the current process that you don't. Ask for their input on how to make changes work in practice, not just in theory.

For more techniques on adapting your communication approach to different team members, check out The Power of Adaptive Communication.

When Improvements Don't Stick

This was my biggest frustration for a long time. I'd implement a change, see good results, then watch performance slowly drift back to the old way.

What I learned is that you have to build improvements into standard work. Don't just tell people about the new process—document it, train on it, and measure compliance with it. Make the new way the official way, not just the preferred way.

Create accountability systems that support the improvement. If the new process requires different behaviors, make sure your measurement and recognition systems reward those behaviors.

I also learned to ask why people might revert to old methods. Is the new process actually harder to execute? Does it require tools or information that aren't always available? If you don't address these practical barriers, the improvement won't last.

Document your improvement results systematically. This creates institutional memory and helps you understand which changes work and which don't. For a comprehensive approach to tracking your improvement efforts, see Keeping a Success Journal.

Measuring Success and Scaling Improvements

Once you've implemented improvements, you need systems to measure their effectiveness and decide when to expand them.

Choosing the Right Metrics

Focus on leading indicators, not just lagging indicators. Lagging indicators tell you what happened (productivity, quality, safety incidents). Leading indicators tell you what's likely to happen (process compliance, near-miss reports, variation in cycle times).

Balance productivity, quality, and safety metrics. It's easy to improve one at the expense of others. Make sure your measurement system captures the full picture of performance.

Create dashboards that drive behavior, not just report results. The best metrics are the ones that help people make better decisions in real time. A dashboard that takes three days to update isn't useful for operational decisions.

When and How to Scale

I don't scale every improvement. Some work well in specific situations but don't translate to other areas or teams.

My criteria for scaling: Does the improvement work consistently across different people and conditions? Can I train others to implement it successfully? Does it deliver results that justify the effort to expand it?

I also learned to avoid the "flavor of the month" trap. When you're constantly introducing new improvement initiatives, people stop taking any of them seriously. Better to focus on fewer improvements and implement them thoroughly.

Build institutional knowledge around improvement processes. Train multiple people on how to lead improvement projects. Create templates and tools that make it easier for others to replicate your success. Document lessons learned so future improvement efforts can build on your experience.

For strategies on capturing and documenting your improvement results as they happen, see Document Your Achievements in Real Time.

What This All Means

Process improvement isn't some mysterious talent that some leaders have and others don't. It's a skill you can learn, and the key is understanding that your job is to facilitate improvement, not dictate it.

The best improvements come from engaging your team as partners in solving problems. When you create the right conditions—safety to point out problems, clear frameworks for testing solutions, small testable changes—your team will surprise you with their insights.

Remember Deming's lesson: if your processes aren't delivering the results you want, the problem is usually the system, not the people. Focus on designing systems that make it easy for people to succeed.

This post kicks off our operational excellence series. Next week, we'll dive into the 5-Why technique for getting to the root cause of problems. The following weeks will cover metrics that actually drive performance and practical workflow optimization strategies.

Everything we cover will build on what we've established here—that improvement is a systematic, team-based approach, not something you do to people.

From Theory to Action

Here are seven practical steps you can take this week to start implementing process improvement fundamentals:

Map one critical process - Pick your biggest daily headache and document how it actually works today. Don't worry about making it perfect—just capture the real flow of work.

Collect baseline data - Spend three days measuring current performance without changing anything. Track cycle times, error rates, or whatever metric matters most for your chosen process.

Schedule team input sessions - Set up 15-minute conversations with frontline workers about improvement ideas. Ask: "What slows you down most in this process?" and "What would make your job easier?"

Design one small pilot test - Pick the simplest suggested improvement and test it with a small group for one week. Keep the scope narrow and the timeframe short.

Create a measurement system - Establish daily tracking for your pilot test metrics. Use a simple whiteboard or spreadsheet—sophistication matters less than consistency.

Document everything - Use the Process Analysis Worksheet to capture learnings and results from your pilot test. Record both what worked and what didn't, along with why.

Plan your next iteration - Based on pilot results, decide whether to scale the improvement, modify it, or try something different. The key is continuous learning and adjustment.

Your team has been waiting for you to create the conditions where their improvement ideas can flourish. These seven steps will help you get started.

Follow me on LinkedIn