Decision Making for New Warehouse Managers: Part 3 - Building a Decision-Making Culture

Build decision-making culture, not individual hero dependency

Walking through your distribution center during peak season, you observe the controlled chaos that somehow transforms into customer orders. At the inbound dock, a team lead is deciding whether to accept a late trailer that could disrupt their schedule. Near the pack stations, an associate is choosing between two packaging options for an oversized item. At the shipping dock, a supervisor is determining whether to hold a truck for a priority order that's running behind. In the span of a few minutes, you've witnessed dozens of decisions being made—each one affecting throughput, quality, cost, and customer satisfaction.

Here's what hit me during one of these floor walks: I had spent months perfecting my own decision-making skills, but the quality of decisions happening around me varied wildly. Some were brilliant—quick, effective solutions that moved the operation forward. Others created bottlenecks that rippled through the entire facility. That's when I realized the fundamental limitation of focusing solely on individual decision-making capability: if you're the only one making good decisions, you've created a dangerous single point of failure.

This post concludes our three-part series on decision-making for warehouse leaders. In Part 1, we explored mastering everyday operational decisions using frameworks like the 2-Minute Decision Matrix. Part 2 tackled high-impact decisions with the SCALA framework. Today, we're taking the biggest leap: building organizational decision-making systems that create sustainable competitive advantage.

The Individual vs. Organizational Decision-Making Gap

During my time managing teams across multiple departments at Amazon, I learned this lesson the hard way. I had become quite good at making operational decisions quickly and effectively. My team's metrics were strong, problems got resolved efficiently, and senior leadership seemed pleased with our performance. But there was a problem I didn't initially recognize: almost every significant decision still flowed through me.

The bottleneck effect was subtle at first. Department managers sought approval for staffing adjustments they could make themselves or escalated process modifications within their authority. Associates waited for guidance on quality exceptions they had the knowledge to resolve. I had inadvertently trained my entire operation to depend on my judgment rather than developing their own.

The breaking point came during a busy week when I was pulled into back-to-back leadership meetings while the floor experienced multiple issues simultaneously. Equipment was down in two areas, a quality concern had emerged, and staffing was short due to unexpected absences. My team had the knowledge and authority to address these issues, but they waited. For over an hour, problems compounded while capable people sought approval for decisions they should have made independently.

Organizations that depend on individual decision-making heroes face critical limitations: bottlenecks that slow response time, inconsistency in standards, knowledge trapped with individuals, and growth constrained by individual capacity rather than systematic capability.

As I discussed in The Art of Delegation, effective leaders build capability in others rather than hoarding decision-making authority. The organizations that consistently outperform competitors develop decision-making cultures, not dependence on individual heroes.

Toyota's Decision-Making Revolution

In my earlier post on Communication Fundamentals, I explored how Toyota's andon system revolutionized production floor communication. Today, let's examine how this same system fundamentally transformed organizational decision-making.

The Toyota Production System emerged from post-WWII Japan's resource constraints, but its innovations in distributed decision-making have become foundational to modern operational excellence. Traditional manufacturing at the time operated on a strict hierarchical model where workers were implementers and managers were decision-makers. Problems were escalated up the chain, often creating delays that compounded into significant issues.

Toyota's breakthrough was recognizing that people closest to problems often had the best information to solve them—if empowered to act within the right frameworks. The andon system wasn't just a communication tool; it was a sophisticated decision-making framework disguised as a communication system.

What made this empowerment possible was the decision-making infrastructure:

Clear Authority Boundaries: Workers knew exactly when they could stop the line and when to escalate. These boundaries were explicit and consistently applied.

Systematic Training: Toyota developed decision-making capability through structured training on problem identification and solution development, not just permission.

Information Systems: Visual management provided real-time information needed for good decisions at the point of decision.

Learning Loops: Every andon pull generated data about decision effectiveness, systematically reviewed to improve both individual decisions and the overall system.

The results were remarkable: higher quality, faster problem resolution, increased engagement, and sustainable competitive advantage that competitors spent decades trying to replicate.

For warehouse leaders, Toyota's example demonstrates that distributed decision-making requires systematic capability, not just empowerment. Freedom to decide must be paired with frameworks for deciding well.

The Three Levels of Decision-Making Maturity

Through observing dozens of warehouse operations, I've identified three distinct levels of organizational decision-making maturity:

Level 1: Centralized Control

Most significant decisions get escalated to management. Team members seek approval for routine adjustments and rarely make independent choices beyond basic tasks.

Advantages: Consistency, clear control, obvious accountability

Disadvantages: Management bottlenecks, slow problem response, team disengagement

Level 2: Guided Autonomy

Clear frameworks enable distributed decisions within defined boundaries. Team members understand their decision authority and operate confidently within established parameters.

Key Elements: Explicit decision boundaries, support systems like templates and checklists, measurement focused on decision quality and speed

Level 3: Cultural Integration

Decision-making capability embedded throughout the organization. Teams self-correct their approaches and continuously improve their decision processes.

Reality Check: Level 3 is exceptionally difficult to achieve. In my career, I've been part of only two teams that truly reached this level. Most operations—including very successful ones—function effectively at Level 2. Reaching Level 3 requires years of sustained effort and exceptional organizational commitment. This doesn't mean we stop striving for it, but realistic expectations about the time and effort required are essential.

Quick Assessment: How often are you interrupted for decisions others could make? Do team members confidently handle routine operational decisions? Can your operation maintain decision quality when key managers are absent?

Building Decision Authority Frameworks

The foundation of Level 2 decision-making maturity is establishing clear frameworks that define "who decides what." This isn't about creating bureaucracy—it's about enabling faster, better decisions by eliminating the ambiguity that causes hesitation and inefficiency.

During my time at Amazon, I faced a recurring challenge with cross-departmental decisions. Issues would arise that affected multiple areas—picking, packing, and shipping—but nobody was clear about who had the authority to make decisions that crossed these boundaries. This led to either prolonged discussions while everyone waited for someone else to decide, or multiple people making conflicting decisions that created even bigger problems.

The solution was developing explicit authority guidelines that mapped decision types to appropriate levels:

Decision Categories: Different types with clear ownership (staffing, process modifications, quality exceptions)

Authority Levels: Specific boundaries for each role (department managers: 15% staffing adjustments within area; team supervisors: process changes not affecting other departments)

Escalation Triggers: Clear criteria for elevation (safety implications, budget impact over $500, multi-shift changes)

The results were dramatic: decision speed increased significantly, conflicts between departments decreased, and team members became more confident in their ability to resolve issues independently. Most importantly, I was no longer a bottleneck for routine operational decisions.

There are some common pitfalls you’ll want to avoid when implementing authority frameworks:

Under-specification: Leaving too much ambiguity creates the same problems you're trying to solve. Be specific about boundaries and criteria.

Over-specification: Creating excessive bureaucracy that slows decisions defeats the purpose. Focus on the decisions that matter most.

Inconsistent Application: Different standards across areas creates confusion and resentment. Ensure frameworks are applied uniformly.

Poor Communication: The best framework is useless if people don't understand it. Invest time in training and reinforcement.

As I explored in The Power of Delegation, effective empowerment requires clear boundaries. Authority frameworks provide these boundaries while enabling distributed decision-making that scales with your operation.

Creating Information Flow Systems

Good decisions depend on good information being available when and where decisions are made. The most effective approach combines visual management with targeted digital systems:

Visual Management Essentials: Real-time metrics displayed at decision points, current state information enabling quick choices, and visual cues helping people recognize when situations require management attention versus independent action.

Technology Integration: Mobile access to information on the warehouse floor, proactive notifications when decisions are needed, and integrated platforms showing complete pictures without system switching.

Cross-Shift Continuity: As I discussed in Communicating Through Shift Changes, effective information transfer is critical for maintaining decision quality across 24/7 operations.

The key is implementing technology that enhances rather than complicates decision-making, as I explored in The Power of Focused Work.

Building Psychological Safety for Decision-Making

Even with clear authority frameworks and good information systems, distributed decision-making fails if people are afraid to make decisions. Fear of making mistakes, blame cultures, and perfectionist expectations create environments where people avoid decisions rather than making them confidently.

This experience taught me that psychological safety for decision-making requires intentional design, not just good intentions. The fear of making mistakes can be so powerful that it overrides logic, expertise, and even explicit authority. Creating environments where people feel safe to make decisions requires addressing this fear systematically.

The Learning-Oriented Response to Mistakes

The cornerstone of psychological safety is how you respond when decisions don't work out. Every poor outcome presents a choice: focus on blame or focus on learning. Your choice teaches your team what's really valued.

I've found that the most effective approach is establishing clear protocols for addressing decision mistakes. When something goes wrong, the first questions should be: "What information did we have at the time?" and "What can we learn to make better decisions next time?" This approach separates the quality of the decision process from the outcome, which may have been influenced by factors beyond the decision-maker's control.

For example, when a team lead's staffing decision results in a productivity dip, the focus should be on whether they used available information appropriately, considered reasonable alternatives, and followed established frameworks. If the decision process was sound but unforeseeable factors created poor outcomes, this becomes a learning opportunity rather than a performance issue.

Proactive psychological safety involves creating opportunities for safe experimentation. Intentionally create opportunities for team members to test judgment on decisions that can be easily reversed—process improvements piloted in single areas, staffing adjustments tested for single shifts, new approaches implemented with built-in review points.

Leadership Modeling That Builds Confidence

Perhaps the most powerful tool for building psychological safety is how you model decision-making yourself. When leaders share their own decision struggles, admit uncertainty, and demonstrate learning from mistakes, it normalizes the reality that decision-making involves judgment rather than perfect knowledge.

I've made it a practice to occasionally walk my team through my own decision process on complex issues, including the uncertainties I'm wrestling with and the factors I'm considering. This transparency demonstrates that even experienced leaders don't have all the answers and that good decision-making is about working thoughtfully with incomplete information.

Building psychological safety connects directly to the principles I explored in my post on Creating a Culture of Openness and Honesty. Trust forms the foundation that makes distributed decision-making possible.

Decision Learning and Improvement Systems

Organizational decision-making capability requires systematic learning that persists beyond individual tenure. During a challenging period implementing multiple process changes, we kept encountering coordination problems where good decisions in one area created unintended consequences elsewhere.

The breakthrough came when we started capturing not just what decisions were made, but why and what broader impacts occurred. This organizational memory revealed patterns no individual could see from their position.

Building Organizational Memory

Focus documentation on decisions with broader learning value—those informing similar future situations, involving interesting trade-offs, or having unexpected outcomes. Use simple one-page templates capturing situation, options, rationale, and outcomes to create searchable repositories.

Systematic decision learning enables pattern recognition that optimizes recurring decisions. Similar staffing challenges every Tuesday due to predictable volume patterns can become standard evaluation criteria rather than unique weekly problems.

Decision coaching focuses on improving decision-making processes—helping structure problems, evaluate options systematically, and learn from outcomes. Combine this with shadowing programs and case study discussions using real decisions from your operation.

Your Complete Decision-Making Toolkit

This series has built a comprehensive capability framework:

Part 1 Foundation: The 2-Minute Decision Matrix for everyday operational choices—enabling quick, appropriate responses to routine situations within clear authority boundaries.

Part 2 Advanced Skills: The SCALA framework for high-impact decisions—systematic approaches to consequential choices involving multiple stakeholders and significant outcomes.

Part 3 Organizational Systems: Cultural frameworks that enable good decisions at every level—authority structures, information systems, psychological safety, and learning mechanisms.

Together, these create decision-making capability that scales with your operation and improves over time.

Implementation Roadmap

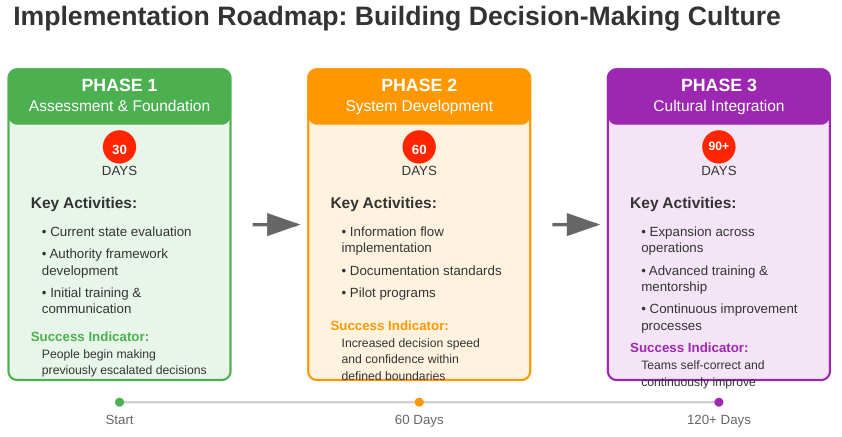

Building decision-making culture unfolds in three phases, each building on the previous foundation:

Phase 1: Assessment and Foundation (30 days)

Conduct honest assessment of current decision patterns and bottlenecks. Create explicit authority guidelines for your three most common decision types. Educate your team on new frameworks and their decision authority.

Success Indicator: People begin making decisions they previously escalated, even hesitantly.

Phase 2: System Development (60 days)

Implement information systems supporting decision-making at key points. Establish documentation processes for important decisions and lessons. Test approaches in pilot areas before full implementation.

Success Indicator: Increased decision speed and confidence within defined boundaries.

Phase 3: Cultural Integration (90+ days)

Expand refined systems across all operations. Develop advanced capabilities through coaching and mentorship. Establish systematic review and improvement processes.

Success Indicator: Teams self-correct decision-making approaches and continuously improve without management intervention.

Series Conclusion

Throughout this series, we've built comprehensive decision-making capability: individual skills for everyday choices, frameworks for high-impact decisions, and organizational systems enabling good decisions at every level.

Individual decision-making skills are the foundation, but organizational decision-making culture is the multiplier. When you invest in systematic capability, you create benefits extending far beyond any single decision or situation.

The warehouse managers who build these capabilities don't just perform better in current roles—they prepare themselves and their organizations for increasingly complex challenges. As automation, e-commerce growth, and supply chain complexity accelerate, the ability to make good decisions quickly and consistently becomes increasingly valuable.

Your legacy as a leader isn't just the decisions you make—it's the decision-making capability you build in others. By creating systems, culture, and capabilities enabling great decisions at every level, you multiply your impact far beyond what any individual leader can achieve alone.

From Theory to Action

Ready to build decision-making culture in your operation? Start with these practical steps:

Conduct a Decision Bottleneck Audit: Track every approval request for one week. Note decision type, time spent, and whether it could have been made independently with proper framework. This baseline reveals where authority clarification has the biggest impact.

Create Decision Authority Guidelines: Document explicit boundaries for each role using the three most common decision types from your audit. Use specific criteria (dollar amounts, percentages, time boundaries) rather than vague guidelines.

Implement Decision Documentation Standards: Establish a one-page template for significant decisions that could inform similar future situations. Review monthly to identify patterns and improvement opportunities.

Build Cross-Shift Decision Continuity: Update shift handover processes to include ongoing decision situations and establish protocols for decisions spanning multiple shifts.

Establish Decision Learning Reviews: Schedule monthly 30-minute team sessions discussing decision effectiveness. Focus on system improvement, not individual performance evaluation.

Develop Decision Mentorship Programs: Pair experienced decision-makers with developing team members. Create shadowing opportunities and regular coaching sessions focused on decision processes.

Create Decision Support Tools: Implement visual management providing information for common decisions. Start with one decision type and expand based on value delivered.

Measure Decision-Making Health: Track time from problem identification to resolution, decision escalation frequency, and team confidence levels. Review quarterly and adjust systems based on trends.

Start with the audit this week—you'll discover surprising insights about current patterns and improvement opportunities. Building decision-making culture is a journey that compounds over time, creating organizations that perform well today while continuously improving their effectiveness.