Operational Problem-Solving: Part 3

Systemic Approaches to Recurring Issues

This is Part 3 of a 3-part series on problem-solving for warehouse and manufacturing leaders. Part 1: Structured Approaches | Part 2: Collaborative Solutions

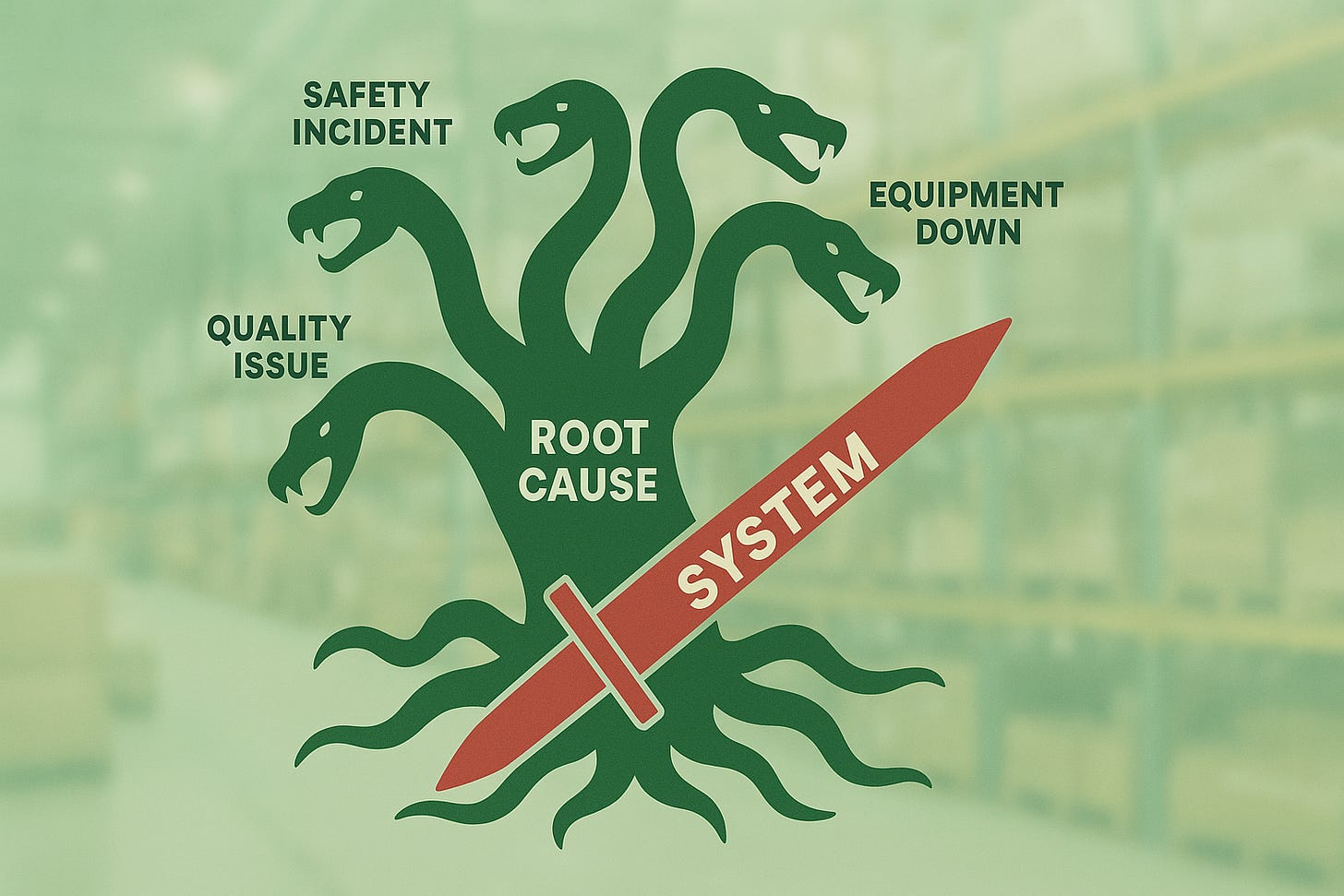

In Greek mythology, Hercules faced the Lernaean Hydra—a serpentine monster that grew two heads for every one that was cut off. What started as a battle against a single opponent quickly became an escalating nightmare of multiplying threats. The harder Hercules fought using conventional tactics, the worse the situation became.

If you’ve been managing operations for more than a few years, you know this feeling intimately.

You solve a safety incident, and two weeks later an identical one occurs in a different area. You address a quality issue on Line A, only to discover the same defect pattern on Line B. You implement a communication fix for the day shift, and the night shift develops the exact same problem.

Welcome to the world of recurring operational problems—the modern manager’s hydra. And just like Hercules discovered, attacking each head individually is not just ineffective; it’s counterproductive. The solution lies not in fighting harder, but in thinking differently about the nature of the beast you’re facing.

This is where we move beyond both individual problem-solving and collaborative approaches into systemic thinking—the discipline of addressing the underlying structures that create recurring problems rather than just responding to their symptoms.

When Individual and Collaborative Approaches Aren’t Enough

Here’s how you know you need systemic thinking: you’ve used the structured individual approaches from Part 1, you’ve tried the collaborative methods from Part 2, and the same problems keep showing up anyway.

The issue comes down to a simple distinction most operations managers never learn to see clearly. Symptoms are the visible problems that grab your attention—incidents, breakdowns, quality failures. Systems are the invisible processes and structures that create the conditions for those problems to happen in the first place.

Symptoms are like the hydra’s heads—obvious and urgent. Systems are the body—harder to see but far more powerful.

Here’s the trap: when production is down and schedules are at risk, you fix the immediate issue and move on. This creates the “firefighting mentality” I’ve written about before—always responding, never preventing.

But during my years managing operations across Amazon, I learned that good intentions to “do better next time” never solve recurring problems. Jeff Bezos put it perfectly: “Good intentions never work, you need good mechanisms to make anything happen.”

When you keep fighting the same problems, you don’t need better intentions—you need better systems. It’s the difference between being a firefighter (responding to problems) and a fire marshal (preventing them).

Same Problems, Different Locations

Let me tell you about a recent experience I had that highlights the difference between treating symptoms and fixing systems.

After teaching half a dozen technical skills workshops for Amazon managers, I noticed that a similar problem was being mentioned in most of my sessions, a mechanical problem that was causing late departures at site after site.

The issue kept popping up. Different times of day, different locations, identical patterns. We weren’t having different problems. We were having the same problem in different places.

Our standardized processes—which created incredible efficiency—also created standardized failure points. The same workflow bottlenecks, the same equipment placement issues, the same communication gaps during shift changes.

This wasn’t a people problem. This was a systems problem.

Instead of developing another incident response protocol, we built what Amazon calls a “mechanism”—a complete process that converts inputs into desired outputs on a recurring basis. Every mechanism needs three parts:

The Tool: We redesigned the physical workflows that allowed these problems to occur instead of just training people to work around them. Early identification systems that caught issues before they became incidents.

The Adoption: We made preventing the problem faster and easier than fixing it. All employees were trained and practiced the preventative methods. Supervisors tracked leading indicators like “problems identified” instead of just incident counts.

The Inspection: Weekly reviews focused on spotting patterns across sites. Dashboards that showed us where similar conditions existed before problems occurred.

Six months later we’ve seen a 13% reduction in late departures (82% reduction coming specifically from mechanical issues) across the entire network. More importantly, we’d shifted from reactive incident response to proactive prevention.

Individual problems need problem-solvers. Complex problems need facilitators. But recurring problems need people who can build systems that prevent problems instead of just responding to them.

How to Spot Problems That Need Systematic Solutions

Not every problem needs the systematic approach. Some issues are genuine one-offs perfect for individual methods. Others are complex but unique challenges that work great with collaborative problem-solving.

The trick is recognizing when you’re dealing with something that keeps coming back.

Here are the four warning signs:

Same Problem, Different Times: Quality issues that pop up monthly. Equipment failures every quarter. Communication breakdowns during every major project.

Same Problem, Different Places: Identical issues across departments, shifts, or locations. When receiving, shipping, and returns all have the same problem, you’re looking at a system issue.

Same Problem, Different People: When Joe makes a mistake, it might be training. When Joe, Maria, and Carlos all make the same mistake at different times, the system is setting them up to fail.

Same Problem, Same Process Points: Breakdowns that always happen during shift changes, peak periods, or handoffs between departments.

The DEEP Framework for Systematic Analysis

When you spot these warning signs, use DEEP to figure out if you’re dealing with a systemic issue:

D - Develop Pattern Recognition

Start tracking problems differently. Instead of just logging individual incidents, look for categories, timing patterns, and common conditions. This builds on the problem logging methods from Part 1, but focuses on themes that span multiple incidents.

During your bi-weekly success journal sessions, spend time looking for patterns in the problems you’re solving. Are you seeing the same types of issues repeatedly?

E - Evaluate Symptoms vs. Systems

Ask yourself: “If I fix this specific problem, will it prevent the same type of issue from happening anywhere else in my operation?” If the answer is no, you’re treating a symptom.

This often requires the collaborative perspective-gathering we covered in Part 2—other people see patterns you might miss when you’re focused on individual incidents.

E - Examine What Enables the Problem

Here’s where the 5-why technique becomes essential. Keep asking “what makes this possible?” until you get to process and structural issues, not just individual decisions.

What conditions, workflows, or policies create the possibility for this problem to occur? What would need to change to make it difficult or impossible?

P - Prevent Through Systematic Design

Build systems that eliminate the conditions creating problems rather than just responding better when they occur.

Use 1:1 meetings to involve key team members in system design. The people doing the work often see prevention opportunities that aren’t obvious from a management perspective.

Quick diagnostic: If you can’t measure prevention (only response), you don’t have a real system yet.

How to Build Systems That Actually Work

Once you’ve identified a systemic issue through DEEP analysis, you need to design all three mechanism components before implementing anything. Here’s how:

Design the Tool

Change fundamental workflows to eliminate entire problem categories. For recurring inventory accuracy issues, don’t just improve your audit process—redesign the physical layout and verification steps to make mis-picks difficult.

At one of our facilities, we had recurring congestion in the pack area during peak hours. Instead of managing congestion better, we redesigned the staging process to eliminate the bottleneck points that created congestion. We used process improvement principles to map the workflow and identify where the backup always started.

Plan the Adoption Strategy

The best tool is worthless if people don’t use it consistently. Make correct actions easier than incorrect ones through training, process design, and clear incentives.

This connects directly to the feedback conversation principles I’ve written about. People need to understand not just what to do differently, but why the systematic approach works better than the old way.

Use your regular team meetings to reinforce adoption. Celebrate when people identify problems before they become incidents. Recognize pattern recognition, not just problem-solving speed.

Build Inspection Loops

Create ways to track whether your system is working before problems occur. As I discussed in metrics that matter, leading indicators (hazards identified, process improvements implemented) tell you more than lagging indicators (incidents that happened).

Set up weekly reviews where you ask three questions: Are people using the new system? Are we getting the prevention results we designed for? Where do we need to adjust?

Start Small, Scale Smart

Pick your most frequent recurring problem for your first system. Design all three components, test in one area, refine based on feedback, then scale to similar situations.

Build learning loops so your system improves over time. What works gets stronger, what doesn’t gets fixed quickly.

Getting Your Team to Think Systematically

Here’s the reality: your team is used to firefighting. Shifting to systematic thinking requires changing daily habits, not just big picture thinking.

Change the Questions You Ask Daily

In your morning huddles, instead of asking “What problems happened yesterday?” try “What patterns are we seeing this week?”

Instead of “How do we fix this breakdown?” ask “This is the third equipment issue this month—what’s creating the conditions for these failures?”

During 1:1 conversations, focus on pattern recognition: “I noticed this is the third time we’ve had this type of issue. What do you think keeps creating the conditions for it?”

Recognize Different Behaviors

Start celebrating when someone identifies a pattern before it becomes a crisis. Acknowledge team members who suggest systematic improvements, not just heroic problem-solving.

Use your delegation opportunities to build systematic thinking. When you assign problem-solving tasks, ask people to look for broader patterns: “Fix this issue, but also tell me if you see similar conditions anywhere else.”

Make It Part of Your Regular Processes

During performance conversations, discuss what systematic improvements each person contributed, not just what fires they fought.

In team meetings, add a “pattern spotlight”—spend five minutes on “What recurring issues did we prevent this week? What systems are working well? Where do we need to build new prevention approaches?”

This connects to the high-performance team principles I’ve written about—you’re building organizational capability, not just solving individual problems.

Practical Example: Changing How You Run Huddles

Instead of the standard format:

“What happened yesterday?”

“What’s the plan for today?”

“Any safety concerns?”

Try this systematic approach:

“What patterns are we seeing in our challenges this week?”

“What prevention opportunities do we have today?”

“What conditions should we watch for that typically create problems?”

Common Obstacles and How to Handle Them

Every systematic approach faces predictable resistance. Here’s what to expect and how to handle it:

“We Don’t Have Time to Build Systems”

This usually comes up when operations are under pressure. Track how much time you spend on recurring problems over a month. Show the math: a week spent building a system often saves dozens of hours throughout the year.

Present it as time investment, not time cost.

“This Feels Like Over-Engineering”

Some problems do need quick fixes. Use DEEP analysis to distinguish between isolated incidents and recurring patterns. Start with your most obvious recurring problem to prove the concept.

“People Won’t Change How They Work”

This is usually a design problem, not a people problem. If your system makes work harder or adds steps without clear benefits, it will fail.

Go back to adoption planning. Make the systematic approach easier than the old way, not just better in theory.

“How Do We Measure Success?”

Focus on prevention metrics: reduction in problem frequency, not just faster problem resolution. Track capability improvement—is your team getting better at spotting patterns and designing prevention?

Document your systematic successes in your success journal. These become powerful examples during performance reviews and advancement discussions.

Your Complete Problem-Solving Toolkit

This systematic approach completes your problem-solving evolution:

Use individual structured approaches for unique issues requiring specific analysis

Apply collaborative team methods for complex problems needing multiple perspectives

Implement systematic thinking for recurring patterns that demand structural solutions

Match your approach to the problem type. More importantly, you’re now positioned as a leader who prevents problems rather than just solving them—someone who builds capabilities that last.

From Theory to Action

Here’s your step-by-step process for implementing systematic approaches:

1. Audit Your Recurring Problems List problems you’ve solved multiple times in the past six months. Look for the four warning signs: same problem across time, locations, people, or process points.

2. Apply DEEP Analysis Choose your most obvious recurring issue and work through the framework. Develop pattern recognition, evaluate symptom versus system, examine enabling conditions, prevent through design.

3. Design One Complete System Plan all three components—tool, adoption, inspection—before implementing anything. Start with a pilot area to test and refine.

4. Track Prevention, Not Just Response Build simple tracking that shows leading indicators. Measure reduction in problem frequency, not just faster problem resolution.

5. Scale What Works Once your first system proves effective, apply the same approach to other recurring problem categories.

6. Build Team Capability Use your regular management processes—huddles, 1:1s, team meetings—to develop systematic thinking throughout your team.

The shift from reactive problem-solving to proactive system-building separates advancing leaders from managers trapped in daily firefighting. It’s the foundation for every strategic capability you’ll develop as your career progresses.

Like Hercules discovering that fire could prevent the hydra’s heads from regrowing, success isn’t about fighting harder—it’s about understanding the true nature of the challenge and applying the right systematic approach.

The question isn’t whether you can solve today’s problems. The question is whether you’re building systems that prevent tomorrow’s problems. That’s what creates lasting value.

Series Navigation

The Complete Problem-Solving Series:

Part 3: Systemic Approaches to Recurring Issues ← You are here

Try the DEEP analysis on one recurring problem this week and share your results in the comments—what systematic patterns did you discover that individual or collaborative approaches had missed?